Internalised Autism vs Social Anxiety: How to Tell the Difference

Why Internalised Autism and Social Anxiety Disorder Often Get Confused

Many clients come to therapy because due to difficulties in social situations. They describe feeling socially anxious, deeply self-conscious, misunderstood, or unsure how to connect with others. Often clients who experience these challenges have been diagnosed with Social Anxiety Disorder, but importantly, Social Anxiety Disorder and internalised autism can look remarkably similar on the surface.

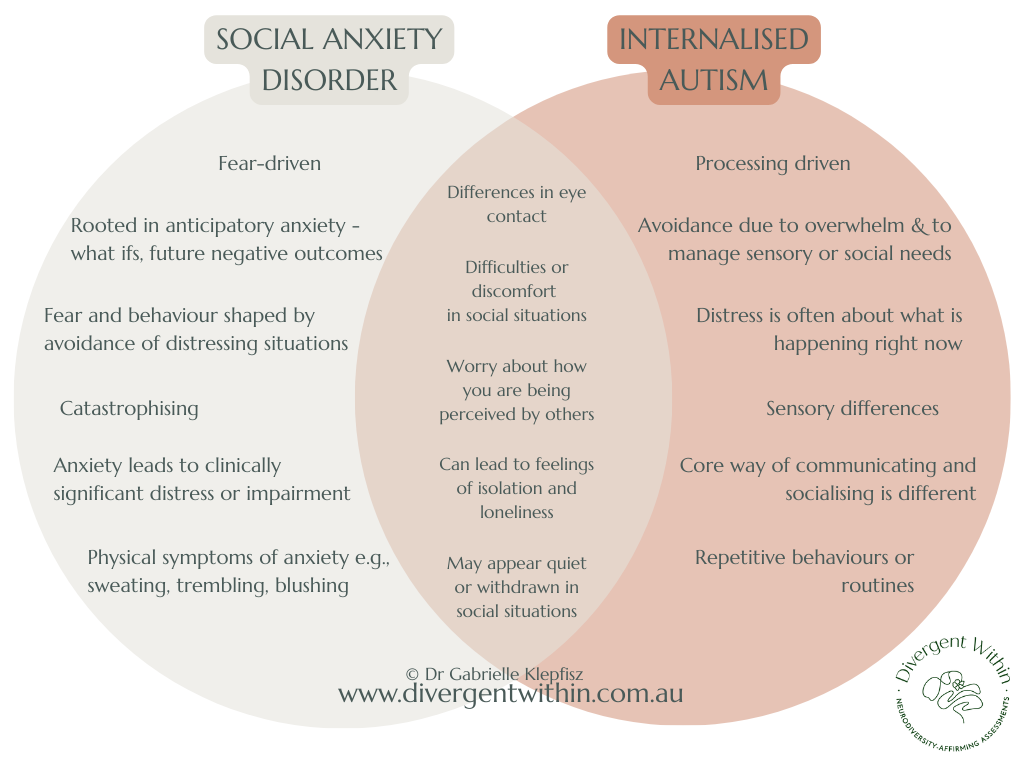

An internalised presentation of autism and Social Anxiety Disorder can both involve discomfort in social settings, difficulty knowing what to say, overthinking interactions, avoiding unfamiliar environments, and feeling disconnected or “different”. And while the two can overlap or even co-occur, the reasons behind these experiences are often very different.

Understanding this distinction matters. When internalised autism is misdiagnosed as social anxiety (which happens frequently, especially in high masking autistic adults), people may receive support that doesn’t address their actual neurotype, sometimes even making things harder.

This blog explores how these presentations differ, why misdiagnosis is so common, and how to begin working out which diagnosis best captures your experiences.

What Is Internalised Autism?

Internalised autism refers to an autistic presentation where the person’s differences are largely experienced internally rather than expressed outwardly. The individual may have learned, often from a young age, to suppress visible autistic traits such as stimming, sensory overwhelm, communication differences, or social confusion. Instead, their effort goes into constant self-monitoring, analysing interactions, and trying to “blend in” and conform to neurotypical expectations.

Because their challenges are less visible, their autistic neurotype can remain undetected for years. Internally, however, the experience can be disabling: it often involves chronic exhaustion, effort attributed to masking, a strong need for routine or predictability, sensory sensitivities, and a deep sense of feeling “different” despite appearing fine on the surface.

Many adults with an internalised presentation of autism describe:

Having to consciously think about every step of a social interaction

Preparing and rehearsing conversations in advance

Feeling overwhelmed by loud, chaotic, or unstructured environments

A long history of being misunderstood or misinterpreted

Intense internal pressure to behave “normally” or not seem “weird” or “odd”

A sense of disconnect between how they appear externally and how hard they are working internally

Internalised autism is not about shyness or low confidence. It is about the cognitive and sensory load required to function in environments not designed for the autistic neurotype.

What Is Social Anxiety Disorder?

Social anxiety is particularly common among masked autistics, with prevalence estimates as high as 50%[1]. This estimate is significantly higher than the 7-13% prevalence in the non-autistic population (NICE, 2013a). Social Anxiety Disorder involves a persistent fear or anxiety about one or more social or performance situations where the individual is exposed to potential scrutiny by others.

Key Differences Between Internalised Autism and Social Anxiety Disorder

Although these two presentations can overlap, they differ in their underlying causes, motivations, and patterns of experience. Some key distinctions include:

The Source of Distress

Social Anxiety: Distress is driven by fear, specifically, fear of negative evaluation, embarrassment, or rejection.

Internalised autism: Distress stems from neurological differences in sensory processing, communication, and social interpretation, not fear itself.

Anticipated vs. Immediate Overload

Social Anxiety: Anxiety often builds before a social situation (anticipatory worry, catastrophising, ‘what if’ thinking).

Internalised autism: Distress is more likely to emerge during the interaction due to sensory, social, or cognitive demands (although anticipatory anxiety and/or dread is not uncommon as well).

Desire to Socialise or ‘Social Motivation’

Social Anxiety: The person usually wants to socialise but feels inhibited by fear.

Internalised autism: The person may want and be motivated to have connection, but often finds socialising effortful, confusing, or draining, regardless of fear.

Social Outcomes

Social Anxiety: Anxiety decreases with repeated, safe exposure to anxiety-provoking situations.

Internalised autism: Repeated exposure without accommodations often increases stress and can lead to burnout.

Lifelong Patterns

Social Anxiety: Often develops in adolescence or early adulthood following specific social fears or self-esteem difficulties.

Internalised autism: Present from childhood, even if subtle, though many adults only recognise the signs retrospectively.

Internalised autism is more likely if the person also has:

Sensory differences (e.g., to noise, textures, light, crowds)

Repetitive behaviours or stimming

A strong need for predictability and routines (including outside of social contexts)

Passionate or highly focused interests

Social communication differences (e.g., difficulty “reading the room”, missing subtext, or needing extra processing time)

A long history of feeling “different” or like they are performing socially

These features are not typical of Social Anxiety Disorder alone.

Why So Many Autistic Adults Are Misdiagnosed With Social Anxiety

There are so many reasons why autistic adults, especially those with internalised or masked presentations, are misdiagnosed with social anxiety. As a clinician, I see this happen frequently. Some of the most common reasons include:

Limited understanding of autism among professionals and in the community

Autism research and diagnostic frameworks have historically centred children, males, and more externalised presentations. Many clinicians were trained before newer understandings of autism emerged -particularly before internalised, camouflaged, or late-identified profiles were widely recognised. As a result, adults who present with subtle social communication differences, intense internal self-monitoring, or a history of “feeling different” are often interpreted through an anxiety-based lens rather than a neurodevelopmental one.

Internalised autism doesn’t always match the stereotypes

Because many adults with internalised autism maintain eye contact, appear warm or articulate, or have learned neurotypical social skills, clinicians may assume they “can’t be autistic”. These assumptions push the formulation toward anxiety, especially when the person reports social discomfort. The more someone has compensated or camouflaged, the more likely autism is missed.

Limited sensitivity of some screening tools

Standardised screening tools were largely normed on populations with more overt or stereotypical behaviours, which means nuanced, internalised manifestations may not be reflected in their scoring. Furthermore, while these tools assess outward behaviours, they rarely capture the cognitive and emotional effort required to maintain neurotypical functioning.

The diagnostic process often relies on self-report, without the right questions

If an autistic person has masked their whole life, they may not recognise their own autistic traits. They might describe themselves as “socially awkward” or “different”, descriptors that clinicians might associate with anxiety. Unless a clinician specifically explores developmental history, sensory processing, communication style, and patterns of masking, autism can easily be overlooked.

Masking makes autistic traits look like anxiety symptoms

Autistic masking, which involves suppressing natural behaviours, rehearsing scripts, copying social cues, or working hard to hide overwhelm, can give the appearance of social anxiety. From the outside, the person looks tense, hypervigilant, quiet, or overly cautious in social situations. Clinicians who aren’t trained in recognising masking often misinterpret these behaviours as anxiety-driven, rather than protective responses developed over years of needing to appear “socially competent” in neurotypical environments.

Autistic distress is often mistaken for fear

When an autistic person feels overwhelmed or unsure how to read a social interaction, the resulting discomfort is often labelled as anxiety. But in internalised autism, the root cause is typically the sensory load, cognitive load, or difficulty intuitively navigating social nuance, not a fear of judgement. Because the outward behaviour overlaps (withdrawal, avoidance, tension, hesitating to speak), it’s easy to assume the distress is anxiety-based.

Many autistic adults have a long history of negative social experiences

Repeated exclusion, bullying, or chronic misunderstandings shape how autistic individuals approach social settings. Over time, this can create learned caution, guardedness, or anticipatory distress that looks like social anxiety but is actually based on lived experience. Without understanding this context, clinicians may focus on the anxiety and miss the underlying neurotype.

How to Tell Which Fits You Better

Anxiety disorders are fear driven and involve distress about what might happen. So, with social anxiety, the person usually feels anxious or fearful about an anticipated or imagined negative outcome (e.g., the “what ifs”). The anxiety causes the individual to overemphasise the likelihood of something bad happening while underestimating their ability to cope. This can show up at a party, when public speaking, eating in public, or even when going on a date.

With internalised autism, the distinct way in which the person experiences the world is what underlies anxiety in social situations. So rather than a fear of being negatively evaluated per se, the person might feel anxious that they will be misunderstood due to their social communication differences; they may feel like they won’t fit in due to valid past experiences of being excluded due to their neurotype; they may worry about the effort they will need to expend to mask or perform socially all evening; or, they may even worry that the environment itself may be stressful due to being crowds or no quiet spaces to which they can retreat.

Of course, the two can co-occur, which makes teasing them apart harder. But it can be helpful to look for those traits that are distinct to autism, in order to determine whether neurodivergence is relevant. For example, does the person present with sensory processing differences or repetitive behaviours/motor movements that would not be explained by Social Anxiety Disorder alone?

Getting the Right Support

Understanding whether you present with social anxiety, autism, or both is important in order to get the right support. With an anxiety disorder, the treatment often involves exposure to anxiety-provoking situations in a graduated way. The idea is that over time, exposure leads to habituation of anxiety. However, if what you are experiencing is underpinned by your neurotype and not a primary anxiety disorder, then exposure does not lead to habituation. In fact, exposure and ignoring one’s needs can lead to increased stress over time, which can contribute to autistic burnout if not properly understood.

Final Thoughts: Understanding Yourself Beyond Labels

Whether you relate more to internalised autism, social anxiety, or a mixture of both, the most important part of this process is developing a clearer, more compassionate understanding of yourself. Labels are not about categorising you. They are tools that help you understand your needs, your nervous system, and the environments in which you function best.

Receiving the right diagnosis can be deeply validating. Many autistic adults describe finally being able to make sense of lifelong patterns, past relational experiences, and the exhaustion they carry from years of masking. Others find that recognising social anxiety allows them to access targeted, evidence-based strategies that genuinely improve their confidence and wellbeing.

Ultimately, this process is not about forcing yourself to change who you are. It’s about understanding how you naturally move through the world so you can support yourself with greater accuracy, compassion, and alignment.

[1] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10559833/

** If you’ve ever wondered whether your challenges are more than social anxiety or quirks, we provide neurodiversity-affirming adult autism and ADHD assessments in St Kilda and online via telehealth Australia-wide **